The Common Third in Social Pedagogy

– creating an authentic learning space through a truly interesting, shared activity, that’s where the magic happens.

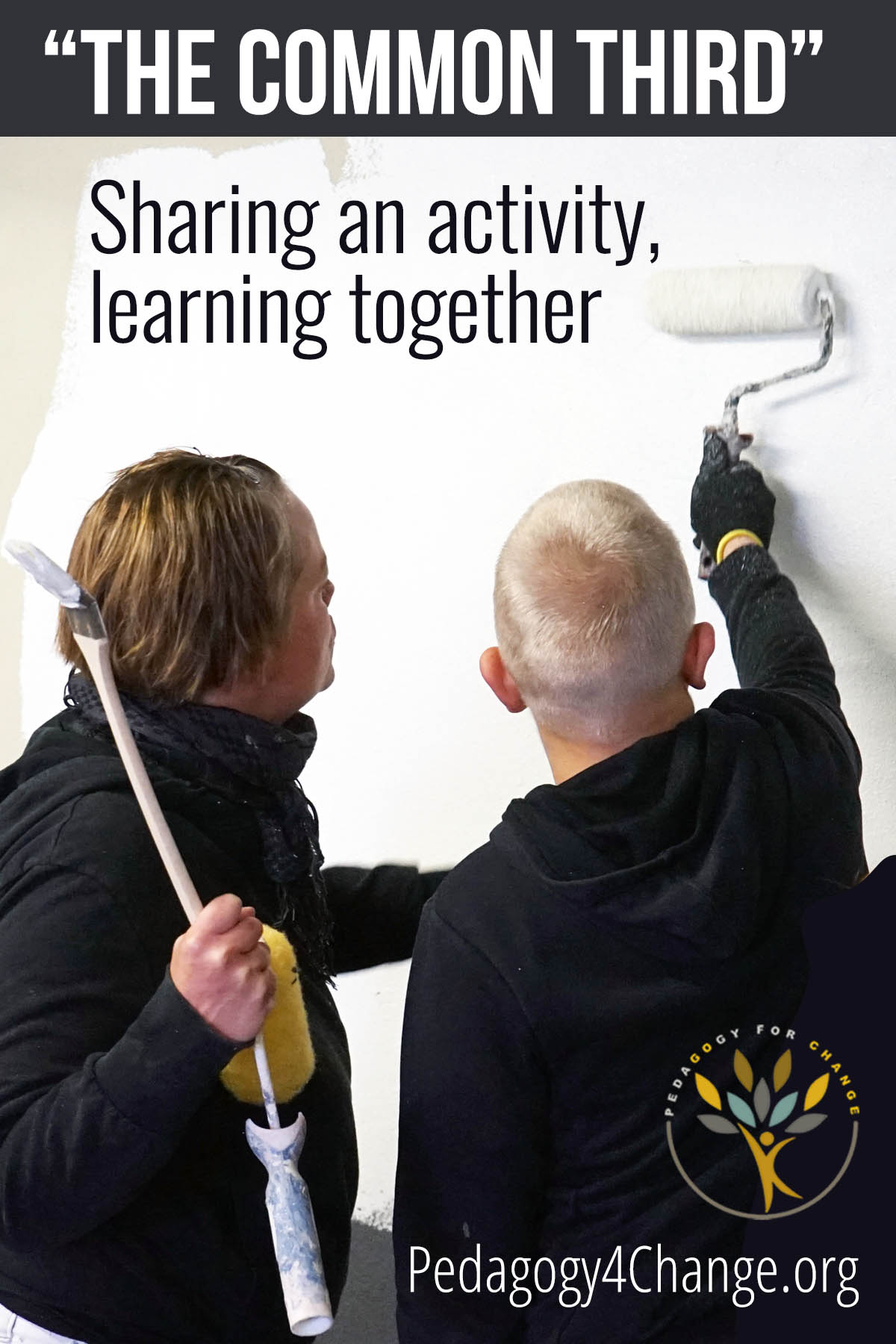

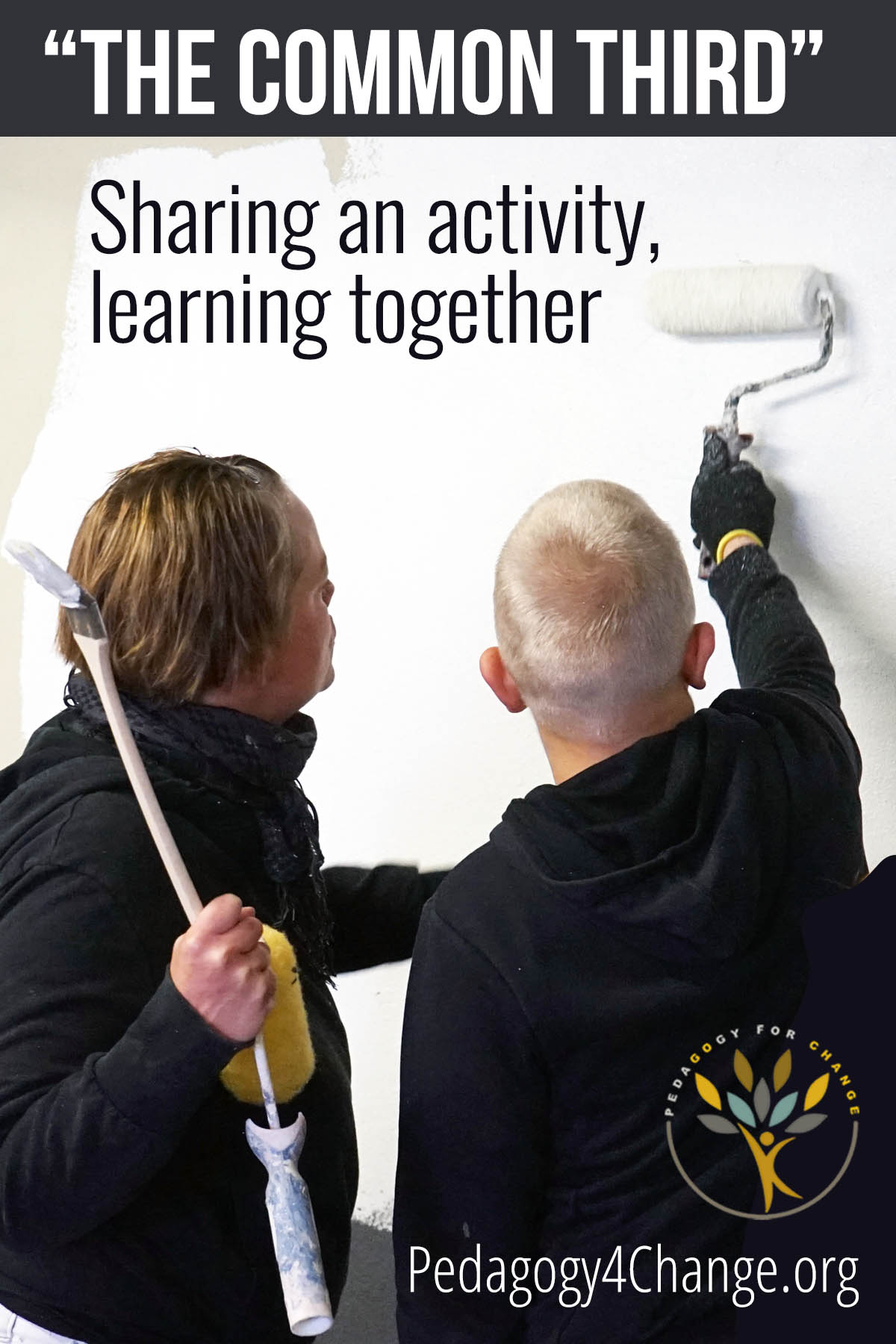

Sometimes two or more people experience something together, or they do something together – solve a task for example. This “something” is unrelated to them as persons and has nothing to do with their relationship. It’s something else. They engage in an activity that both of them are interested in, and in this learning space of shared activity the magic happens. In Danish pedagogy this phenomenon is called “the common third”.

Example one: Building kites

A primary school teacher builds kites with a bunch of children. They start with simple diamond kites, but as the days go on, their kites become increasingly advanced. They borrow kite building books from the library and try out different models. One day they decide to build a new kind of kite, a particularly large and intricate construction. None of them have done it before, but by now all of them have experience with the kite building techniques. They now how to craft thin wooden sticks, cut paper, tie knots, and use glue – and how to measure and adapt the materials as needed.

Example two: Bowling with the lads

A social worker who works with special need parents in a family project goes bowling once a week with the fathers in the group. All of them like to do get together about this activity and while they are bowling, they sometimes get to talk a bit. These men who are not so keen on talking about personal or family matters are more comfortable with doing a physical activity together – where they can meet as equals.

Example three: Making it through rough weather

A practitioner of social pedagogy has gone fishing with a group of youth from a facility for juvenile delinquents. They’re on a fishing boat and the weather is rough. Usually, the atmosphere between the youngsters and the pedagogues is aggressive and sullen. These youngsters don’t trust grown-ups in general, and particularly not pedagogues. But, out there at sea they are together about solving an important task. The harsh conditions and the hard work require their full attention. They work together and communicate in a respectful way, without reservations or negative attitudes.

Dilemmas in pedagogy

When a practitioner of social pedagogy has the role of looking after others, they inevitably assume some degree of responsibility for these people’s well-being and development. Often, this type of pedagogical work is riddled with dilemmas, because essentially the people on the receiving end have had little say in the matter. Sometimes the child / young person in question hasn’t asked to be looked after and they may feel that pedagogues are intruding people interfering with their lives.

This is inevitably an asymmetrical relationship where it is the responsibility of the social pedagogue (or educator) to manage the unequal power structure. The pedagogue needs to recognise their position of power as part of their pedagogical responsibility but at the same time respect that their “client” is a fellow human being whose dignity is paramount.

One way to do this is by identifying some areas where the asymmetrical power relationship, pedagogical considerations, or personal issues, aren’t on the agenda. Instead, a completely different cause or project is put centre stage – something both pedagogue and young person care about and like to do – a common third.

An authentic shared learning space: THE COMMON THIRD

So, the common third is central if we wish to create an authentic shared learning space. It requires us to show our true colours and to be self-reflective, open, and sharing. We need to bring in our personal interests and our humanity as important resources. A common third is an activity in which we as practitioners of pedagogy and the young person are genuinely interested. It doesn’t matter which of us is the more experienced, knowledgeable, or talented – what matters is that the activity enthuses both parties and that we like to engage in it together.

”What makes the Common Third particularly important is that it sees us and the child as learning together. An equal relationship means that we both share a common potential for learning and growth, which makes the opportunities for Common Thirds almost endless: the activities could be not just those that we as the adult might be better in, but also those that the child might be more expert in and can teach us, or even activities that we have both never tried and can thus learn about together.” ~ ThemPra

It’s the creative process that matters

A successful Common Third learning process requires that everyone involved participate on equal terms and participate in all project phases – for example planning, preparing, adjusting, evaluating, and concluding on the whole thing.

This process is valuable, not only the practical outcome or result, but the process itself. Work processes are fundamental human phenomena – perhaps it is even what sets us apart from other species. We have the ability to make plans and to carry them out, step by step. Through our creative efforts way can change our circumstances and set our mark on the world, imprint our values and ideas on it. We can cook a tasty meal, plant flowers, paint a house, learn a song with our band and feel happy about our achievements.

For a process to be truly satisfactory we need to be involved in the entire process. It doesn’t work if all we get to do is to perform what others have decided.

Therefore, it is important that we as practitioners of social pedagogy do not make assumptions about “what would be a nice activity for the youngsters” without investigating what they are interested in. However, this presents us with another dilemma: Many teenagers, especially those with psycho-social issues or suffering from insecurity and low self-esteem are most likely to shrug their shoulders and say “I dunno” if you ask them what they are interested in.

So – we need to accept that identifying that golden Common Third activity requires hard work, imagination, and persistence on our part. And importantly, we need to be inquisitive and listening so we discover those little signals where a young person in passing lets us understand that they would really like to arrange a Halloween party, or look after rabbits, or join an eSports team. Sometimes, we as practitioners of social pedagogy need to step out of our comfort zone and take up an activity we normally wouldn’t engage in, and perhaps realise that it is in fact fun.

Enthusiasm is contagious

It isn’t enough that we identify an activity to be “a third” – it also needs to be “common” to be of real value. In a teaching and learning situation it is not the teacher’s enthusiasm for children or their education that will enthuse others. But when the biology teacher gets completely engrossed in his subject while identifying a rare insect or goes all-in with an experiment, he is likely to win his students over and make them interested, too.

So, share your passion with others. Talk about it, show your results, share your enthusiasm, and let everybody see how happy it makes you. Make no mistake – your sheer love and fascination with a subject matter or activity can be contagious.

Working towards better relationships with Common Third activities

Not all types of human interaction are positive. Some negative phenomena are power struggles, malicious joy, bullying, arrogance and reciprocal negative expectations. There is often a tense atmosphere at facilities for juvenile delinquents, where the communication between social educators and youngsters can be riddled with negative expectations.

These types of problematic human interactions where there is a lack of basic trust and flaring emotions can be difficult to correct. Here, a common third activity can be very useful – something that will distract from personal matters and internal conflicts, a football game, a concert, or something else that is a neutral or safe common ground, even if it is quite brief.

It gives the participants the opportunity to relax, and the opportunity to forget about differences, disagreements, and hostilities. The common third activity can bring people of different views or backgrounds together about something concrete, and over time this working relationship can result in a heightened level of respect for the other.

Helpful insights

Most social educators would agree that The Common Third works as an ‘equaliser’ within a group and creates a positive foundation from which further development can take place.

Since common third activities create shared discovery and experiences for its participants, they also give social educators the opportunity to discover unknown potentials. In this way common third activities provide practitioners of social pedagogy with helpful insights and observations which can be used in future work.

Based on an article first published by Michael Husen in 1996.

What is The Common Third?

Getting together about something which is not about

(1) the people involved, or

(2) their relationship, but something else – namely

(3) “a common third”.

Coined by Danish philosopher Michael Husen.

The Common Third in a nutshell

In Danish social pedagogy “The Common Third”, as described by philosopher Michael Husen, is a commonly used concept which is used about a range of activities, be it sports, arts, animal husbandry or exploring the big outdoors – hiking, mountain biking or sailing.

It indicates that an activity is neither only the teachers’ / pedagogy practitioners’ project, nor an activity to please the pupil / child or young person, but something more and beyond. It is an activity or interest which enthuses and engages both of the parties – a common “third”.

A perfect “common third” is an equalising activity where the boundaries between who is the “teacher” and who is the “learner” are erased, because the activity demands the full attention of the practitioners involved – because everyone is struggling to keep up with the reality of the situation. As a result, they learn something new, together.

What is Pedagogy for Change?

The Pedagogy for Change programme offers 12 months of training and experiencing the power of pedagogy – while you put your skills and solidarity into action.

Studies and hands-on training takes place in Denmark, where you will work with children and youth at specialised social education facilities or schools with a non-traditional approach to teaching and learning.

In short:

• 10 months’ studies and hands-on training in Denmark, working with children and youth at specialised social education facilities or schools. At the same time yo will study the world of pedagogy with your team – a group of like-minded people. You will meet up for study days every month.

• 2 months of exploring the reality of communities in Scandinavia / Europe, depending on what is possible – pandemic conditions permitting. You will travel by bike, bus or perhaps on foot or sailing.

• Possibility to earn a B-certificate in Pedagogy.

Original article by Michael Husen

Read more about the common third in this newly translated article by philosopher Michael Husen himself.

This article is a slightly abbreviated translation from the original Danish of the chapter “Det fælles tredje”, in Benedicta Pésceli, ed.: Kultur & pædagogik, Copenhagen 1996, p. 218-232.

GREAT PEDAGOGICAL THINKERS

Axel Honneth

Through recognition, human beings develop self-confidence, self-respect, and self-esteem. The theory of recognition was developed by German philosopher and educator Axel Honneth.

Astrid Lindgren

Astrid Lindgren’s thoughts about children were provocative in the 1940s, and her approach to childhood as a phenomenon is progressive, even today.

Lev Vygotsky

Interaction with peers, imitation, collaborative learning and other social interaction is key to how the human mind develops, according to Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky.

Maya Angelou

In times of injustice and hardship, Maya Angelou’s call for humanity, unity and resilience teaches us many important life lessons. Her works inspire hope through action.

James P. Comer

“No significant learning can occur without a significant relationship.” Really? Does Dr. James Comer mean that students need to be close to their teacher to learn something?

Jean Lave

Jean Lave is a social anthropologist and learning theorist who believes that learning is a social process, as opposed to a cognitive one – challenging conventional learning theory.

Søren Kierkegaard

Making choices and taking action are at the very core of existentialism. By taking on these responsibilities, as human beings – we find the meaning of life.

Maria Montessori

Children prefer to work, not play. This is one of the main ideas of Maria Montessori, a trailblazers of early childhood education. “The child who concentrates is immensely happy” she noted.

Sofie ‘Rif’ Rifbjerg

Brought up in the countryside Sofie Rifbjerg knew intuitively that fresh air, free play & a deep respect for children’s own agency was paramount for their positive development.

Paulo Freire

Freire’s pedagogy was originally developed for the oppressed adult illiterates of Brazil, but it also inspired teachers and social educators all over the world. Liberation & solidarity are key.

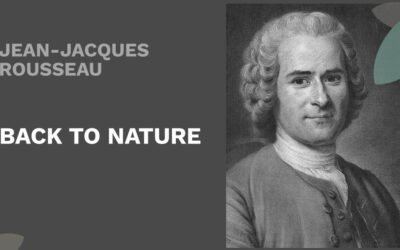

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Rousseau wrote Émile, or On Education, 250 years ago – but the pedagogical principles described in this novel still have much to offer modern educators.

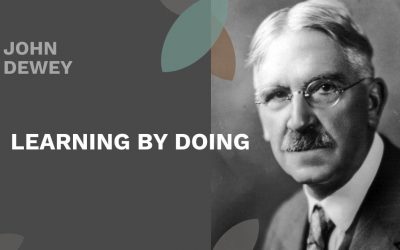

John Dewey

Education, teaching and discipline are lifelong social phenomena and conditions for democracy, according to acclaimed American philosopher John Dewey.